About the Society

The Dunedin Amenities Society is New Zealand’s oldest environmental Society and was established in October 1888. Conceived on October 15th 1888, the Society is New Zealand’s oldest and longest running environmental organisation. It’s an enviable record of longevity and relevance which any organisation should be justifiably proud, and one that the Society will no doubt celebrate with the public of Dunedin. As an organisation the Society has made a significant mark on the city through its development of public spaces, consistent environmental advocacy and vocal support for the protection of a landscape unique to where we call home. Sit on a seat in a public park and admire the trees and there’s every chance that the seat and the trees were donated and planted by the Society in the last 125 years.

Several key events before 1888 helped drive the foundation of the Society in Dunedin. The city had grown in both wealth and population though the boom of the gold rush and the rapid growth of the commercial sector, but there was still a rough frontier aspect to many parts of the city. The uncontrolled development of quarries, roads, land clearance for firewood and grazing and the pollution of the harbour and its tributary streams by abattoir and tanneries were major issues in the development of the city’s environmental consciousness. The Otago Daily Times described Dunedin in 1887“…Go where you will, the natural beauty of hill and valley, wood and water, meet you in all directions. But with all this loveliness in our surroundings, it is very doubtful whether one could anywhere find a community of the size of Dunedin with a less worthy appreciation of the pleasantness of the place wherein their lines have fallen. We are forced to this conclusion, uncomplimentary as it is to ourselves, from the supineness and indifference with which we see the natural beauties of our city and suburbs wantonly, wastefully, some might almost say criminally destroyed.”

The burgeoning city development had inextricably scarred the landscape and depleted the natural resources that were both admired for their natural value but also for their financial and personal gain. There was no clearer indication that this type of activity was a blight on the new city’s residents than in the case of the Dunedin Town Belt. Developed as part of Kettle’s 1848 survey, Dunedin’s Town Board was largely hamstrung during the 1850’s by a lack of funds to protect or preserve the Town Belt. The discovery of gold in 1861 saw the reserve used by squatters and as a source of timber and firewood, and while the Town Belt was not vested in the City Council until 1865, the Council’s management was often strongly criticised well into the 1880’s. The public outcry over the condition and management of the Town Belt was reported in the Otago Daily Times 1887; “It is high time to arrest the process of denudation that is going on in the Town Belt and to make it more available as a place of recreation for the people than it is at present.”

The importance of the landscape for biodiversity and natural resources (particularly water quality) had become a hot topic for Dunedin’s citizens up to the late 1880’s. Internationally, the Victorian age was a period of massive environmental change, and one where economic exploitation of natural resources was driven by the development of global trade and colonisation. Correspondingly, there was also an upsurge in the interest of natural history and botanical science, where amateur and professionals alike scoured the globe for new and exciting discoveries. It’s an odd juxtaposition between the expansion of the industrial age economy and the discovery of the natural world, but that driving interest would have an important influence on the development of the Society.

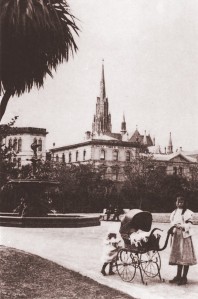

Patriotism and a developing sense of nationalism also played a part in the creation of the Society. Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1888 was foremost on the mind of Society co-founder Thomas Brown when he raised the issue of a suitable demonstration of patriotism for the Queen at Thomlinson’s Paddock (now Jubilee Park) in 1887. The state of the inner city in particular “the triangle” (now Queens Gardens) was also an area that the media and community had lamented on. Its position in relationship to the railway and original railway station near Cumberland Street were deemed as a public disgrace for the entry point of the developing city. With the appointment of the New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition to Dunedin in 1889 the improvement of the inner city was looked on as an essential way to promote the township while the event took place.

In September 1888 Dunedin lawyer Alexander Bathgate read an address to the Otago Institute entitled “The development and conservation of the amenities of Dunedin and its neighbour-hood.” Bathgate outlined a vision for Dunedin that was so detailed in its construction that he apologised to his audience for “frightening you by the extent and magnitude of my programme.” What Bathgate outlined was both the protection of the existing natural landscape and the enhancement of the urban built environment in the developing city. It was a vision that blended the conservation of native biodiversity and landscape with the call home syndrome of “practical and prosaic colonists.” Bathgate’s model for the foundation of the Amenities Society was based on the establishment of the Cockburn Association in Edinburgh in 1875. In 1805, Lord Cockburn had lamented the apathy Scottish people had for the protection of their city and its heritage. On the demolition of one Edinburgh building Cockburn wrote “It was brutishly obliterated without one public murmur. A single individual proclaimed and denounced the outrage, but the idiot public looked on in silence. Reverence for mere antiquity, or even for modern beauty on their own account, is scarcely a Scottish passion.”

Bathgate particularly worried that the apathy for the preservation of biodiversity and heritage that so angered Lord Cockburn in Edinburgh would become prevalent in Dunedin. Indeed Cockburn had written that the destruction of trees was a Scottish example of “hereditary bad taste.” Bathgate challenged his Dunedin colonial audience in a similar vein, stating; “I fear we have inherited more than the names of our town and its streets, and that a portion of the hereditary bad taste and apathy has fallen to our lot.”

Bathgate’s address was clearly a “state of the environment” and it brought clearly into focus what many others in Dunedin were thinking, and by October 1888 the Dunedin Amenities Society had been formed. Bathgate would play a leading role in the Society and would help found the official Arbor Day in New Zealand among other things. The Society had emerged in a backdrop of local concerns for the environment at a number of levels. Firstly, a concern for the aesthetic of the landscape and the discovery of natural biodiversity through the Victorian passion for science. Secondly, it was a utilitarian concern for the preservation of natural resources that provided colonists with a lifestyle they had grown to enjoy. Thirdly, there was a growing sense of community and civic pride where colonists wanted positive open space for recreation and to knock off the rougher colonial edges of the developing city.

The message that Brown and Bathgate promulgated is founded on fundamental values of environmental protection, enhancement and conservation for the long-term betterment of Dunedin and its residents. Sometimes the methodology has changed as we advance further towards a better understanding of science and technology, but at its heart of the Society’s advocacy those core values have not been altered and have remained a constant in its activities and thoughts for 125 years.

Created by the enthusiasm and vision of Alexander Bathgate and Thomas Brown the Society looked to preserve the natural character and beauty of the city while seeking to make improvements to the rough edges of the then colonial City of Dunedin. By the end of 1888 the Society had 245 members and sought to involve itself in conservation and development of the new city

The Society became active in the development of Queens Gardens and the construction of the Wolf Harris fountain, it assisted in the redevelopment of the Octagon as well as the creation of Jubilee Park. It also tirelessly lobbied for the protection of the Town Belt, the city’s sand dunes and the creation of open space and parks throughout the city. Many of Dunedin’s parks and monuments today are the result of the early work of the Amenities Society to provide amenities and recreational opportunities for its citizens in those early years.

The Dunedin Amenities Society has continued to be active over the last 126 years raising funds for amenity projects lobbying the City Council and other agencies to protect and preserve many of the important environmental and heritage areas of the City. Some of its most recent projects include the development of the gardens at the historic Dunedin Railway Station and the upgrade of the historic Wolf Harris fountain now retained at Dunedin Botanic Garden. The Society continues to support many community organisations and often assists with donations of funds to support these organisations. With a strong historical tradition the Society hopes to play an active part in the protection and sustainable development of Dunedin for another 100 years.

The gardens at the railway station are a delightful interlude within the city and the Society is justifiably proud of the final result. The area is visited by many people who enjoy the sun and the grass and that chance to unwind on a hot day.

The Society’s involvement with the fountain goes back to the development of Queens Gardens before the fountain made its way to the Botanic Garden. The late John Perry worked with local engineers to make some of the pieces for the restoration.

So the Society has a deep history entwined in the conservation of the natural environment as well as the development of the amenity landscape of the city.

The Dunedin Amenities Society

The Dunedin Amenities Society